Many tourists visiting Japan from overseas might have hope to see or experience something about samurai. Tokyo must be one of the right places for your desire because Tokyo was the capital of the most powerful samurai government in history. Katana (Japanese swords) and Kabuto & Yoroi (a set of samurai armor) are inevitable when discussing samurai. I already explained about Kabuto & Yoroi in the previous post. So now it’s time to talk about Katana, also known as Token.

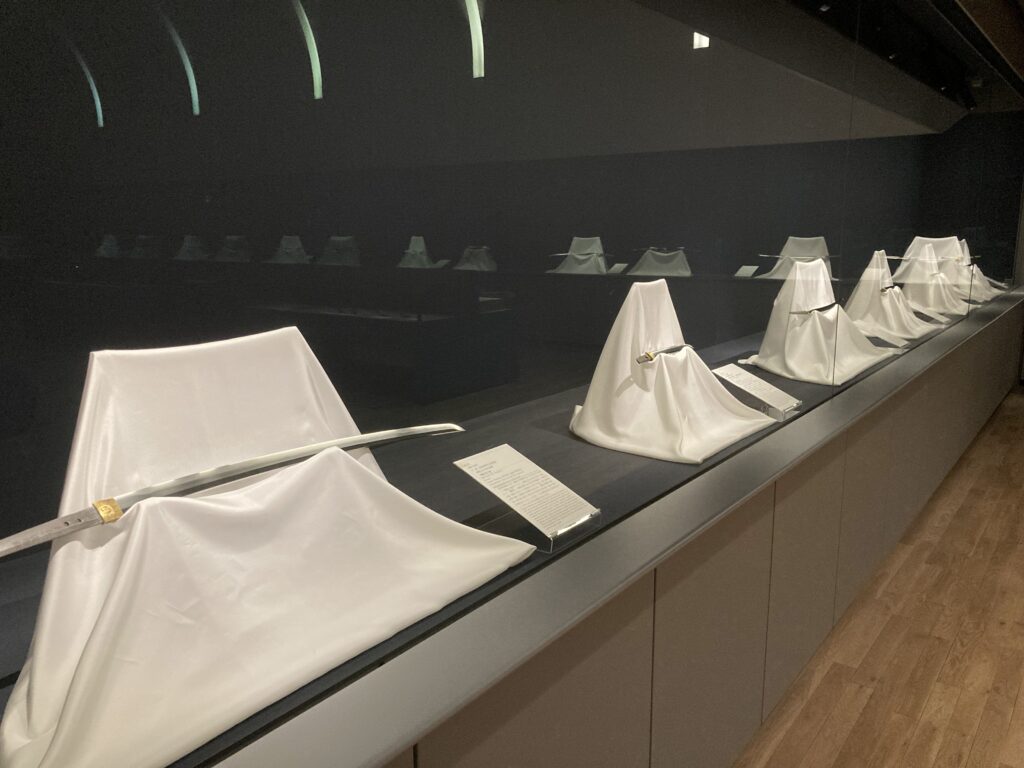

The best place to view and learn about Token is the Japanese Sword Museum in the Ryougoku area. It is a three-story building north of the former Yasuda Garden, with an information area on the first floor and two exhibition floors on the second and third floors.

In the information area, you can watch the video of the Katana crafting process. Unfortunately, it is only spoken in Japan, but it’s still worth watching because the video is well-edited and helps you get a clear image of the crafting process. Furthermore, it is free of charge for visiting all facilities on the first floor. You can see the regular and particular themed exhibitions of a variety of Katana displayed, respectively, with an admission fee of 1,000 yen for adults and free for 15 years or younger.

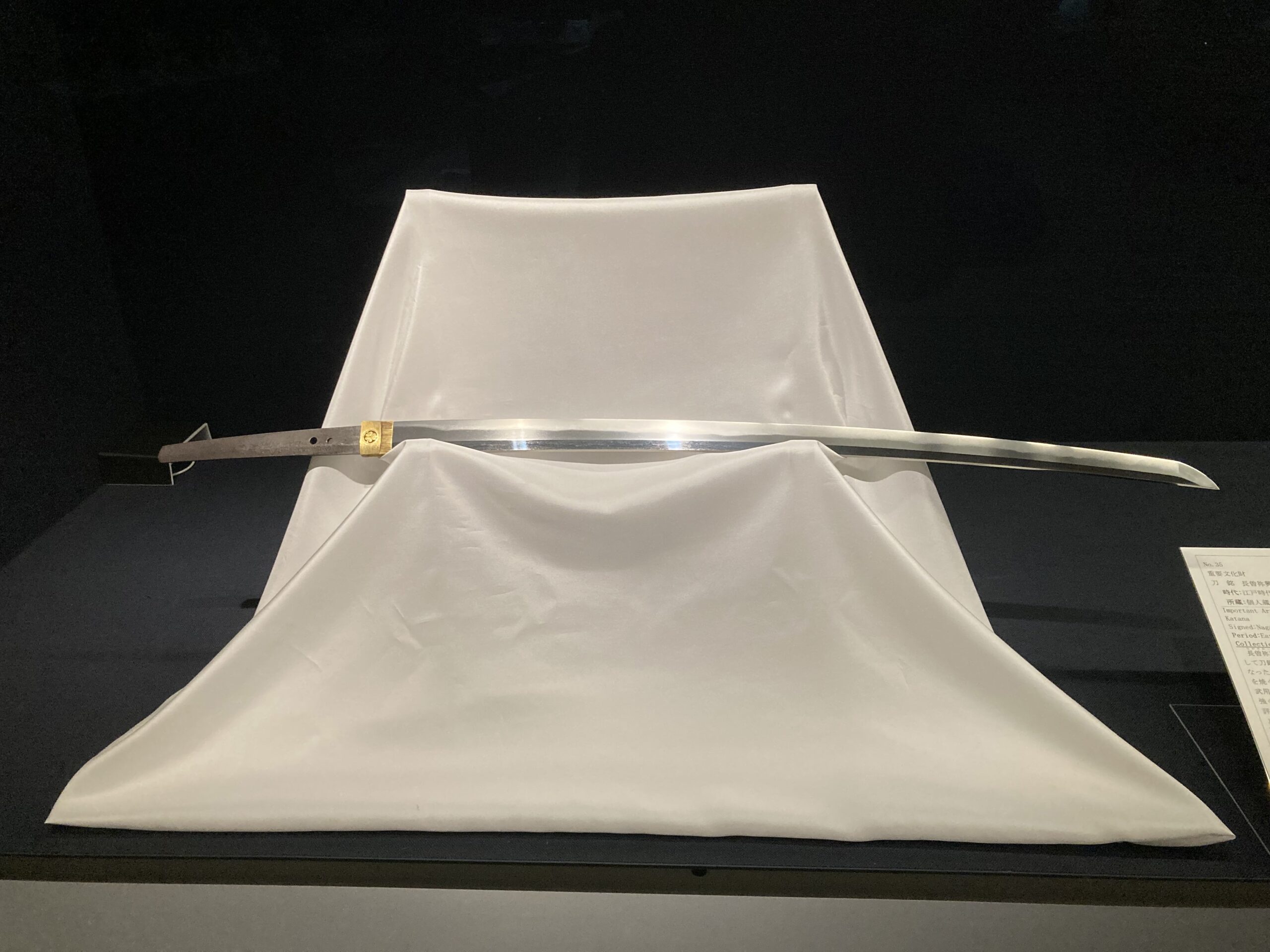

There are two types of Japanese swords: Tachi and Katana.

The Tachi was the sword that commanders or high-ranked soldiers wore from the 12th to the 15th century. It was relatively more extended than the Katana and gradually curved toward the point. The commanders used their Tachi on horses, and the Tachis needed enough length for the commanders to reach their opponents. They also needed to avoid the tip touching the horse’s hips; otherwise, horses would shake them off. So, before the 16th century, the commanders and soldiers sheathed their Tachi with their blade edges down for the reasons mentioned above.

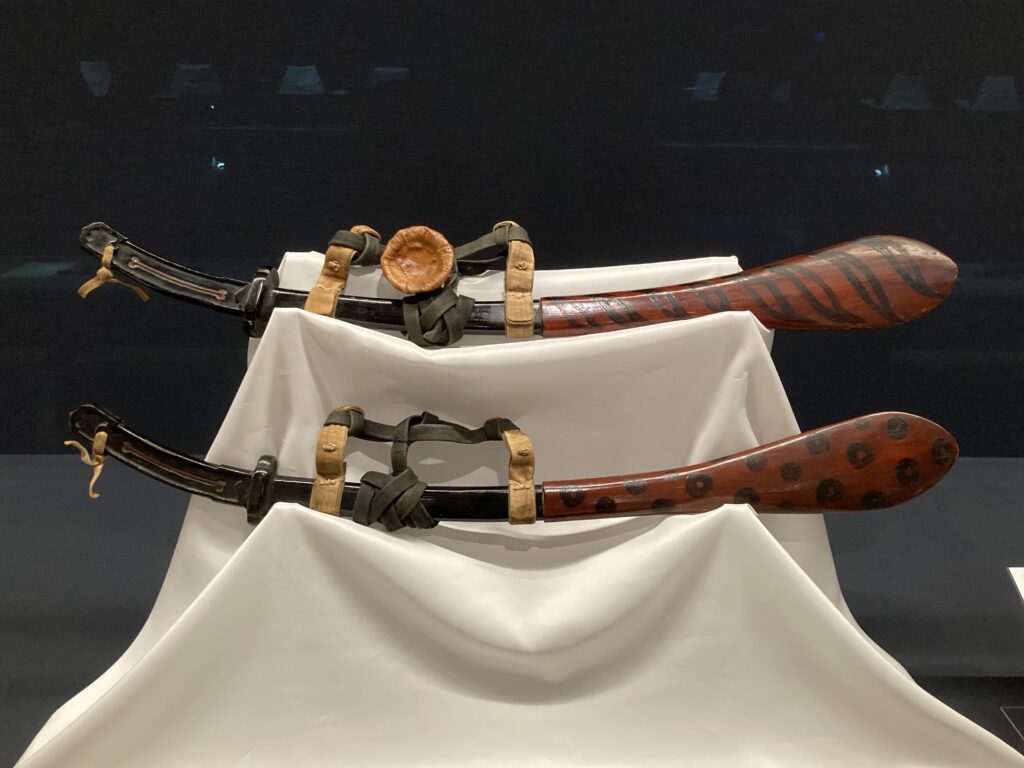

The sheath and blade are delicately decorated with Tachi. It’s because Tachi also had a ceremonial purpose since the samurai forces of the time came from aristocratic families.

On the other hand, after the 16th century, the samurai started using relatively shorter swords, Katana. Katana was made from Tachi, which gradually became shorter and shorter in the process of being sharpened for maintenance, and finally, they got down to Katana’s size. It does not mean a recycling purpose, but it has practical and functional reasons. In the 17th century, the samurai’s battle turned into a struggle with systematic formations and eventually led to close combat between them. In those fights, the longer the swords they used, the more complex the battle became. That’s one of the reasons for shorter swords. The samurai also wore their Katana with the blade edge up in the sheath. It also helped them draw their Katana more smoothly and swiftly against a sudden attack on the ground.

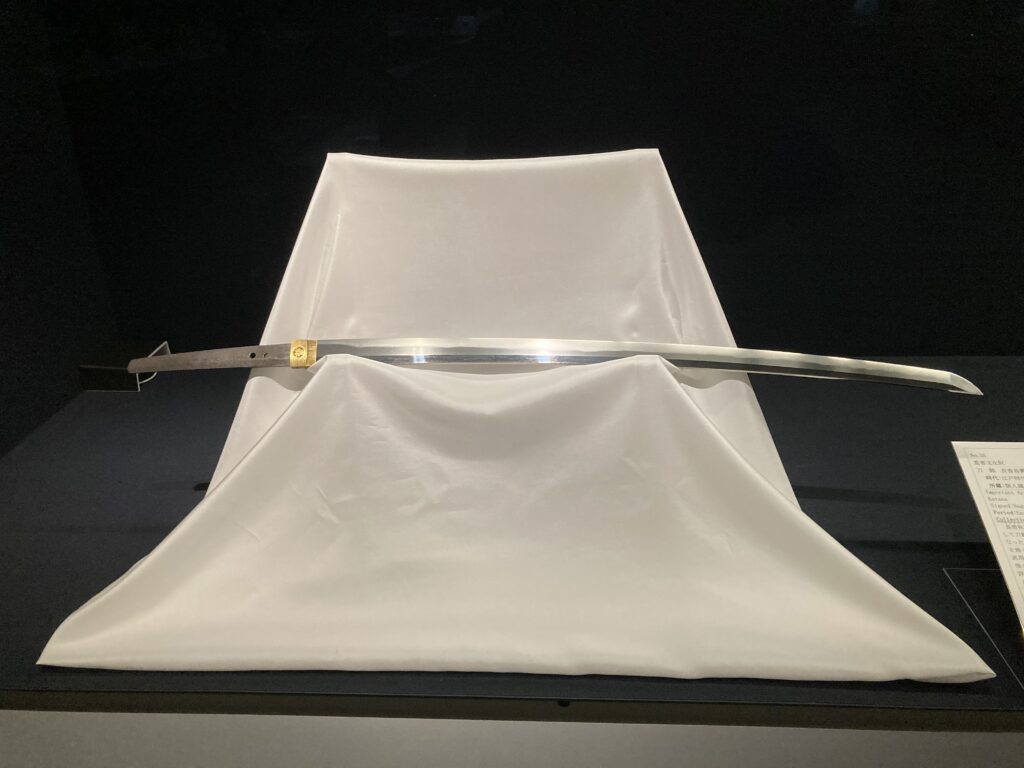

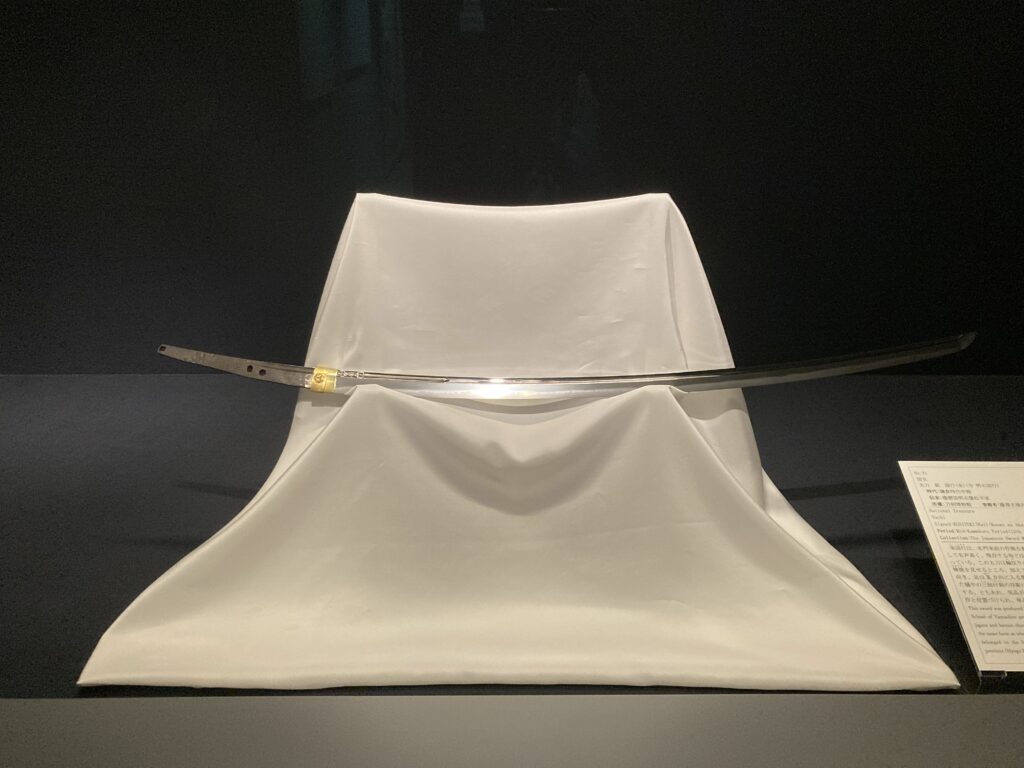

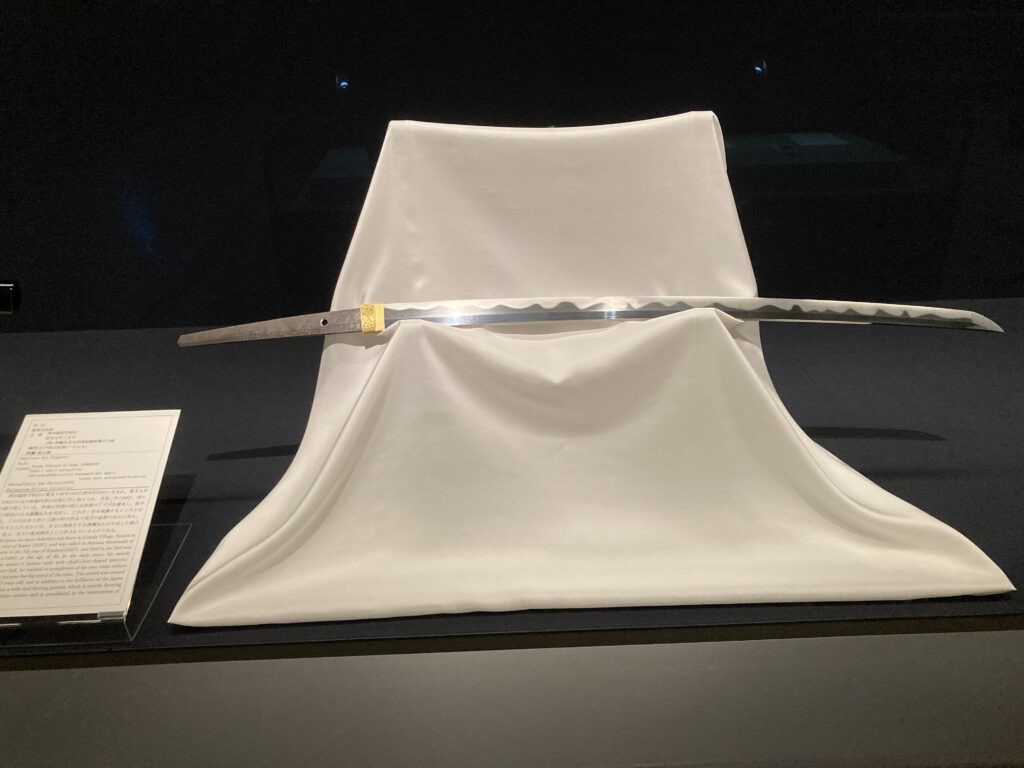

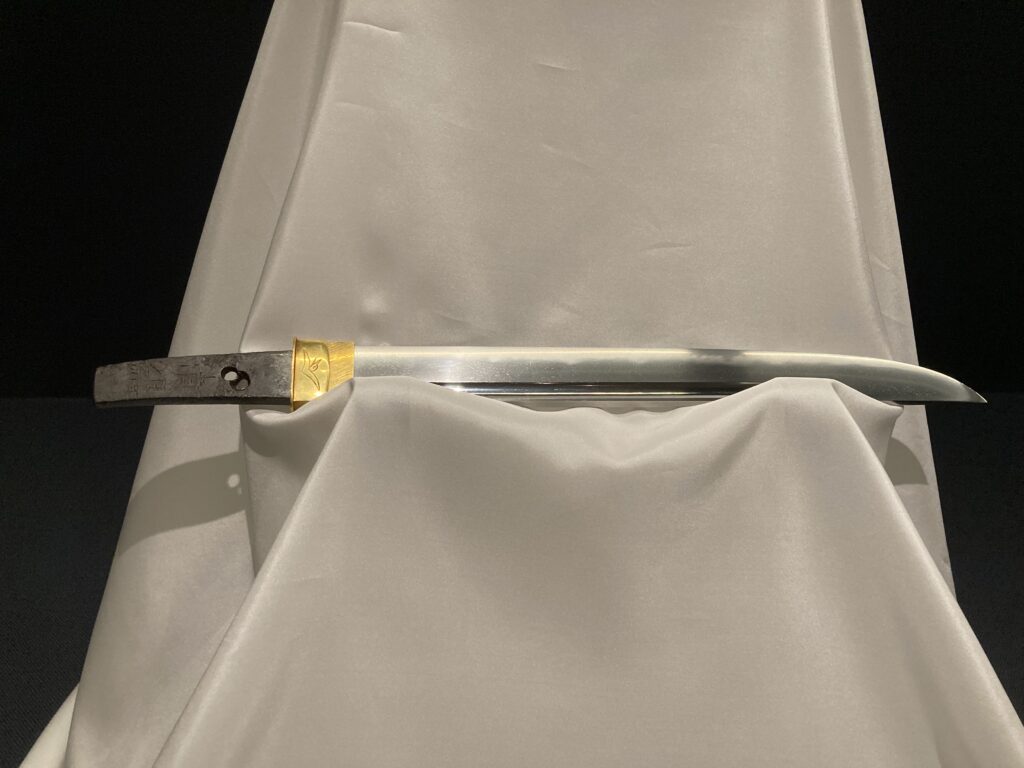

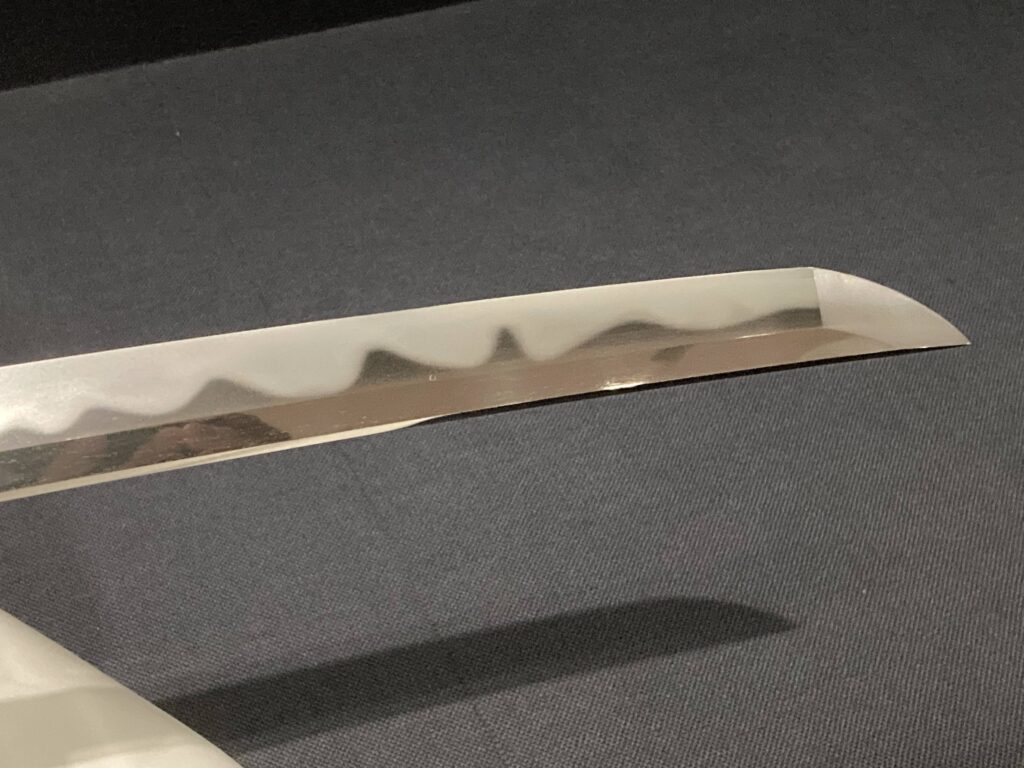

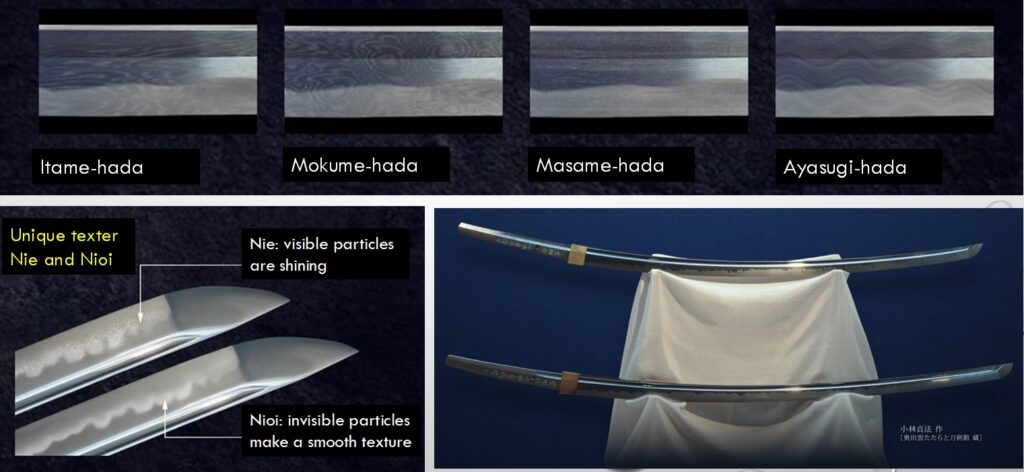

Japanese swords are not only essential weapons but also have aesthetic value in the arts. Could you look at the wave-like pattern on the blade? The white cloud seems to be floating on edge, giving me a sense that something magical is protecting the samurai. This beautiful pattern is created from multiple layers of the sword’s structure and a skilled sharpening process. Many Japanese sword enthusiasts love admiring the patterns on the blades and find their own aesthetic preferences in each sword since no similar pattern exists, and they are so unique.

Wave-like marks are categorized into four groups: Itame-hada, Makume-hada, Masame-hada, and Ayasugi-hada. Depending on the sword-smithing process, they appear on the sword blade respectively.

Of course, samurais prioritize sword strength and resistance to hard smashes with other swords during fights, but recent Japanese sword lovers appreciate their aesthetic marks. Japanese swords attract sword lovers, particularly with their unique textures, Nie and Nioi. Nie has visible particles that create cloud-like marks, while Nioi has invisible particles that make the blade look smoother.

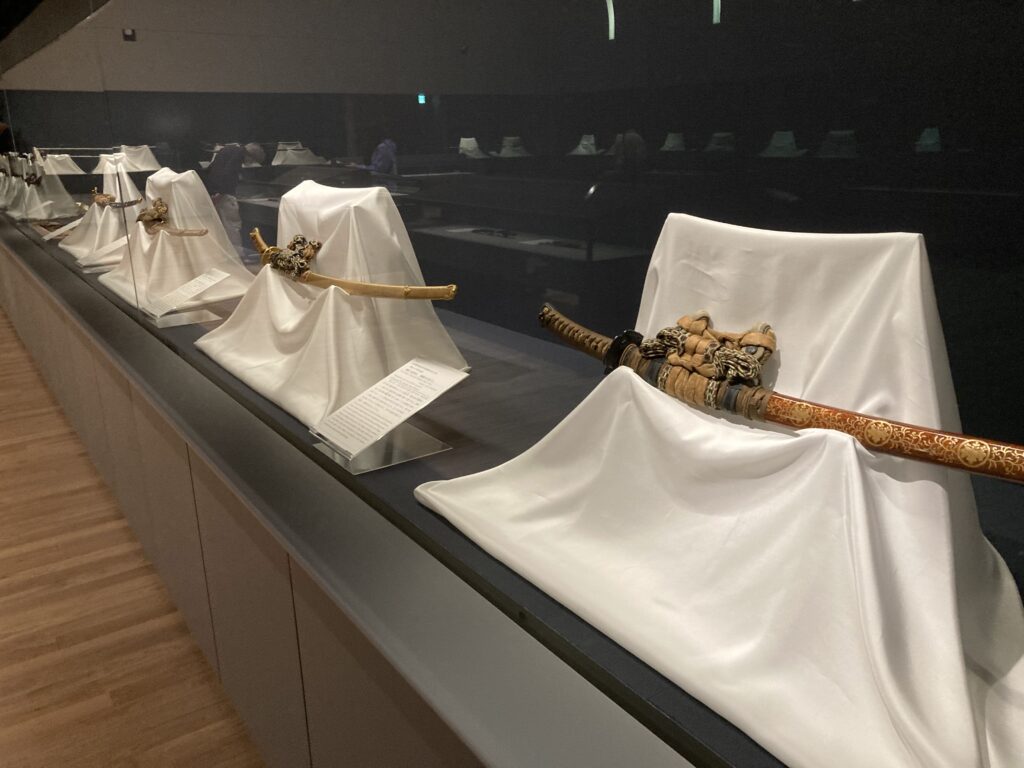

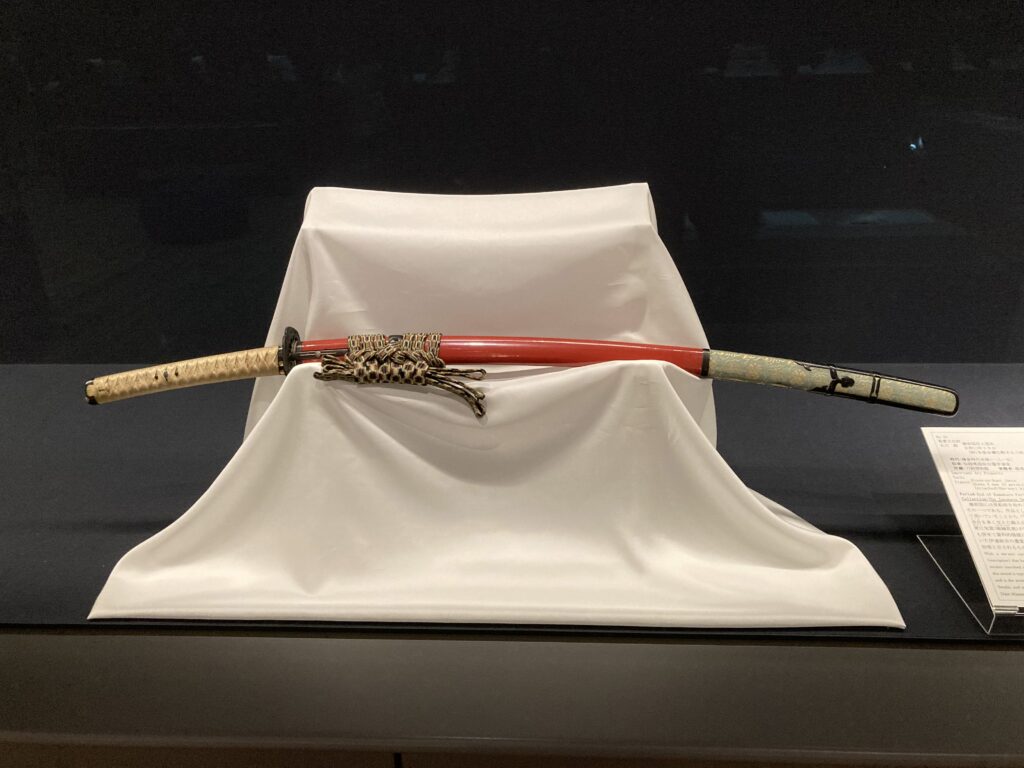

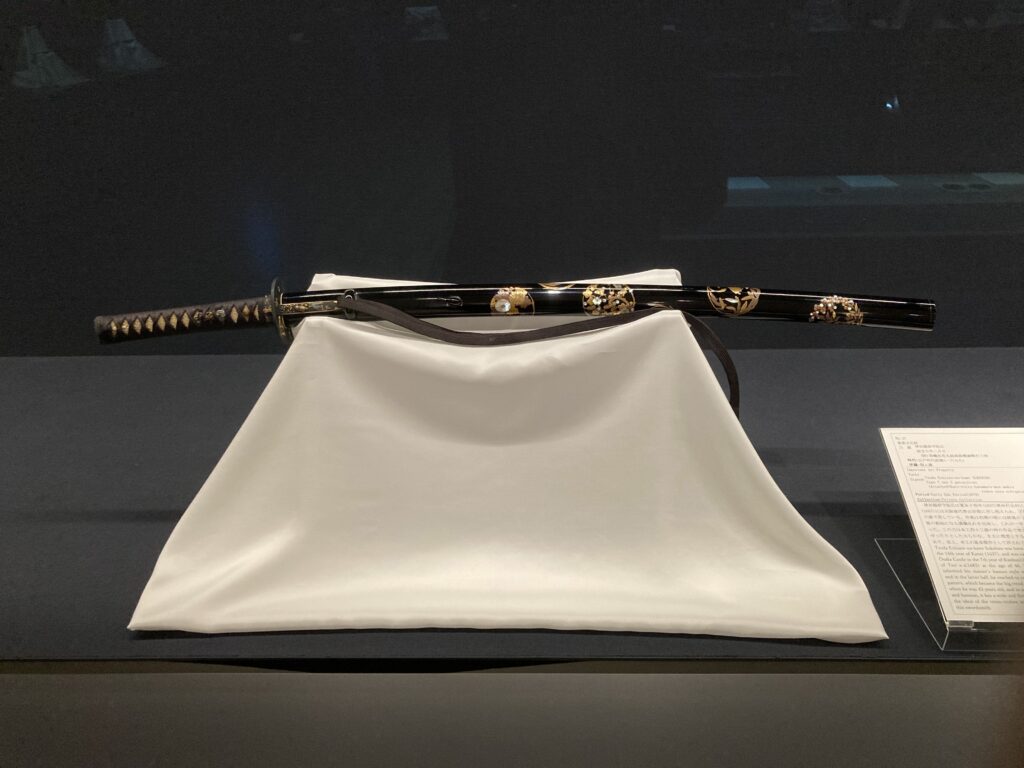

Another artistic characteristic of the Japanese sword is the decorations, especially on the sheathes and around grips. Please look at the following photo, which shows a set of Katana, a long and short sword. Katanas usually have a simple and practical design because they were carried by samurai soldiers who believed simplicity and functionality were most important on their battlefields.

The photo below shows a set of Tachi for the ceremonial competition, in which soldiers ride horses and contest their riding and sword skills. The sheathes and outer items were well decorated since the event was often performed in the shrines for ritual purposes.

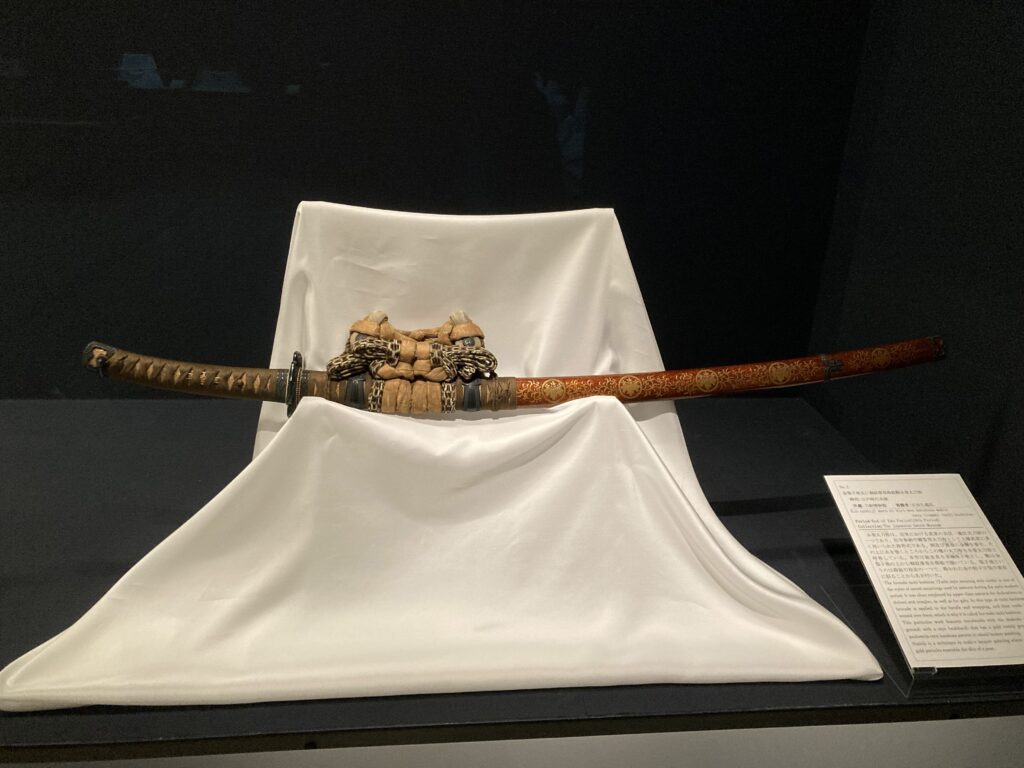

The following two Tachis in the sheathes seem relatively simple, but you can find elaborative designs. The red-orange one is not a monotone color. It has impalpable yellow dots on the red surface, giving a warm feeling to us. The second one has a vine running on the sheath’s surface, which creates emblems.

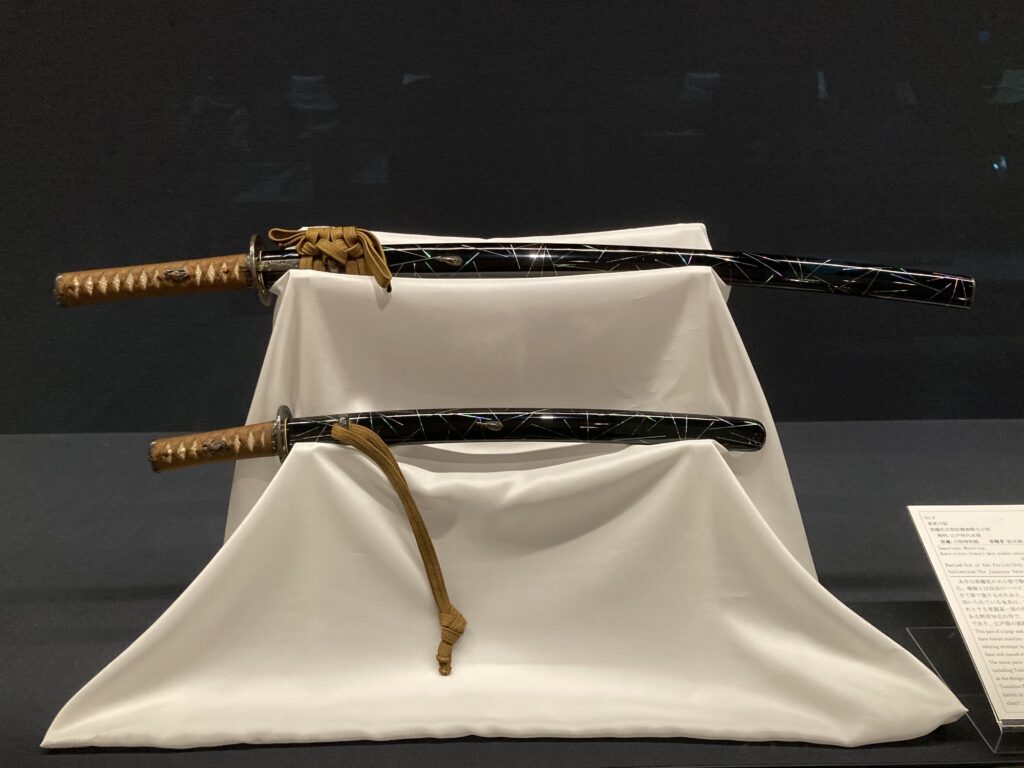

The following two Katana in the sheathes are not colorful, but gold lines on the black surface add to the impression of the samurai’s solid power and seem to represent practical functions for the fights.

Okay, let’s move to the sword-crafting process.

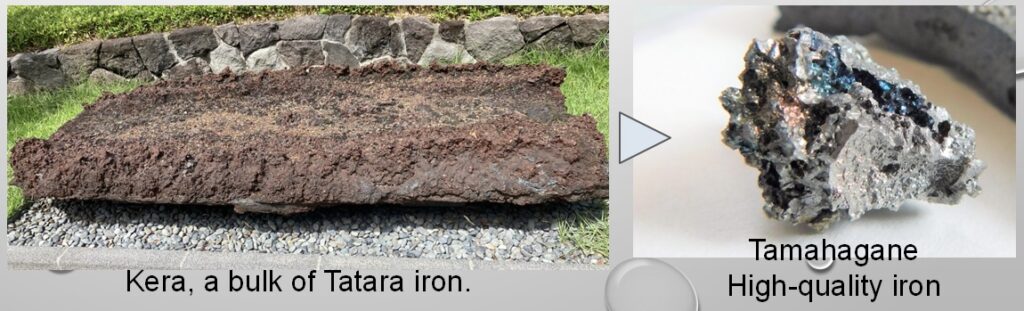

The first lesson of the Japanese swordsmith is about the primary raw material, Tatara iron. If you are a big fan of Ghibli movies, you might have heard of Tatara in the film The Princess Mononoke, where women are working to blow air into a primitive iron furnace called “Tatara.” The furnace Tatara pours out Kera, a bulk of Tatara iron, and then only high-quality parts in Kera are extracted for smelting Tamahagane, the highest quality iron essential for Japanese wordsmiths.

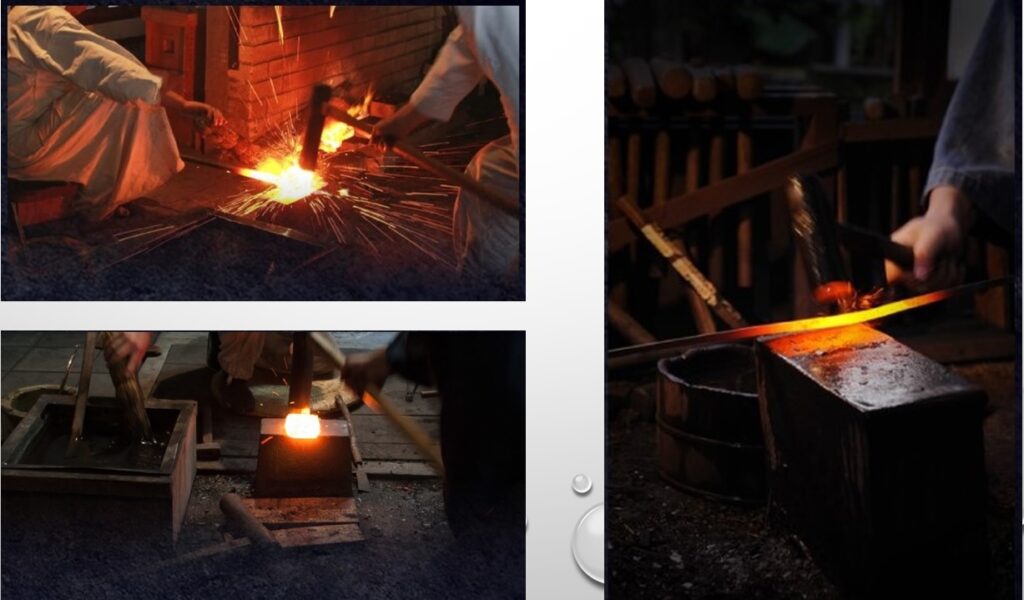

The base material of the Japanese sword blade is called “Kawagane.” Through 15 times being melted, quenched, and beaten, the Kawagane has a laminated structure of more than 30,000 layers, which acquires the contradicting properties of hardness and extreme resilience, creating the beautiful texture of a Japanese sword. Let’s see the Kawahagane smelting process.

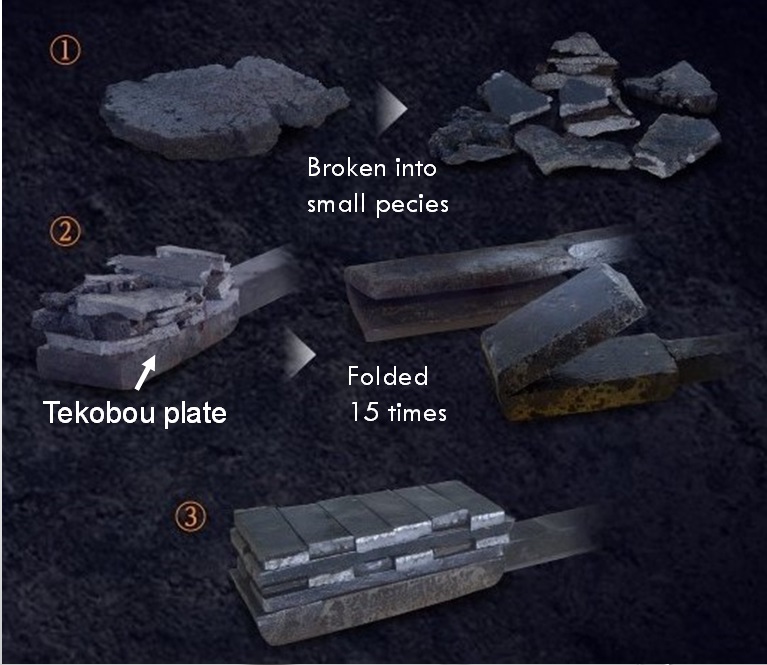

The process of sword smithing

1) Hit the heated Tamahagane with a hammer to make it thin and break it into pieces.

2) Small pieces of Tamahagane are placed on a Tekobou plate, heated, hammered into a flat shape, then folded back and further sintered. Repeat the process 12 to 15 times.

3) The Tamahagane that has gone through the above process approximately 15 times is cut into small plates and then piled, heated, and forged. The appearance of the sword’s surface changes depending on how the small Tamahagane plates are arranged at this time. It creates a beautiful wave-like pattern on the blade.

Here is a video about the Japanese Sword Museum uploaded to YouTube. It helps you get a brief image of the museum visit.

Information

Location: 5-minute walk from the Ryogoku station on the JR Sobu Line

Map: https://maps.app.goo.gl/b8HteydC6fPubskq9

Open: 9:00 to 17:00, Close on Monday and New Years Holiday

Fee: 1,000 yen for adults, free for 12-year or younger

Thank you for reading my post.

If you need an English-speaking guide to explore Tokyo, please click “Contact me!” below. I am willing to help you create an unforgettable private tour. Let’s enjoy amazing Tokyo with me!

Please also leave your feedback on this post in the comment box at the bottom. I am willing to hear your opinions, requests, and suggestions.

Please click the links to get updated via my X (former Twitter) and Instagram.

X (former Twitter): https://x.com/ToruGuide

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/toruhigaki/

Please visit the related post below.

Comment