Kyu Shiba Rikyu Gardens is one of my recommended spots for international tourists in Tokyo.

First, it is just next to the Hamamatsu-Cho station on the JR Lines, so it is easy to access, and you don’t need to worry about getting lost. Most importantly, it is a typical Daimyo Garden, which means the garden created and developed by samurai lords, Daimyo. Kyu Shiba Rikyu Garden is a relatively smaller traditional Japanese garden than others in Tokyo. Therefore, you can enjoy walking around it for less than an hour, maybe half an hour, which is great for tourists who want to save time visiting many other sites in Tokyo during the day. Because of the small size, you may worry that it might be an unimpressive experience. It does not matter, actually. I guarantee you that it is still full of the tastes and preferences of traditional samurai lords’ gardens.

Traditional Japanese gardens are categorized into three groups: the Zen style, the Imperial aristocrat style, and the Daimyo style. The first one, also often called the stone garden, focuses more on quietness and calmness for Zen practitioners. The second has maintained more elegant and sophisticated tastes, favored by ancient imperial families and aristocrats in Kyoto since the 13th century.

Finally, the Daimyo Garden comes. It emerged in samurai society after the 17th century, especially in Edo, former Tokyo, the ancient samurai capital. Kyu Shiba Rikyu Garden has the essential tastes of the Daimyo Garden. Still, due to its unique location near the seaside, it has a slightly different taste from other Daimyo Gardens, such as Rikugien Gardens and Kyu Furukawa Gardens, that I recommended in the previous posts.

The Kyu-Shiba Rikyu Garden was designed so that visitors could enjoy its beauty and splendor while walking through it. One of the vital set-ups is the pond in the center of the garden, which naturally guides visitors to go around it. The walkers can catch various scenes everywhere along the pond, which helps keep them from being bored during their stalling. Another significant factor is that the pond was filled with seawater until 1923. There was a channel to the sea inlet to bring seawater into the pond, and the sea water level there varied as the sea tide changed. So, it could have created diversified landscapes as the water level changed. Unfortunately, the garden’s outside land has been reclaimed since the restoration project was started to rebuild Tokyo, which was devastated by the Kanto Great Earthquake in 1923, and there is no longer a connection between the pond and the sea inlet, so it became a freshwater pond.

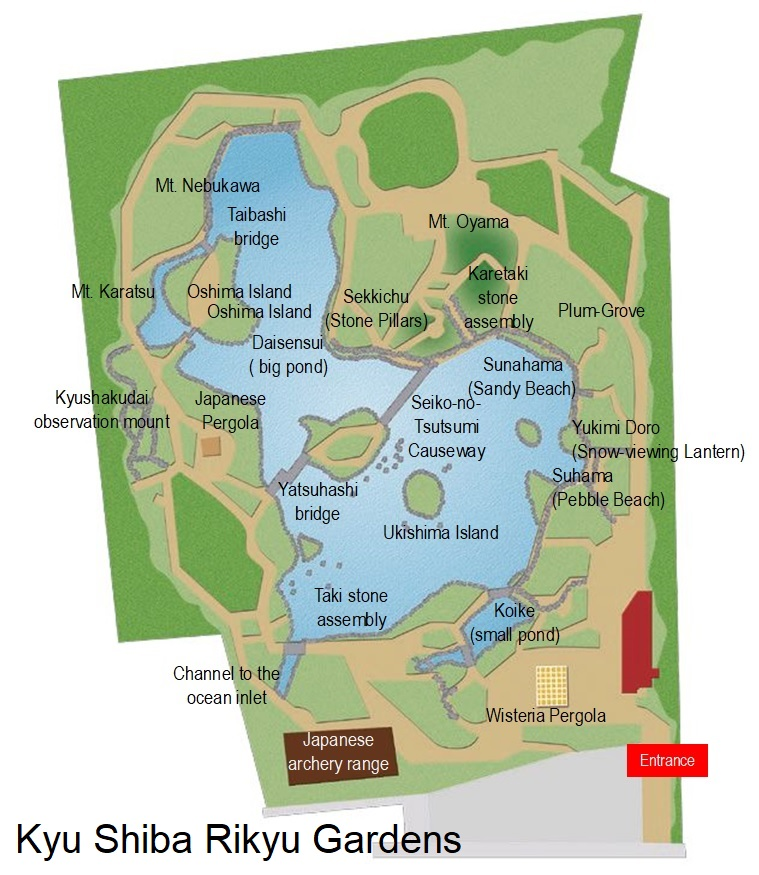

Let’s start a virtual walking tour around the pond anticlockwise on this post.

First, we pass the Koike, a small pond, and move toward the big pond, Daisensui. You can soon find Ukishima, literally meaning the floating island, in the center of the Daisensui. It was a day in November, so Yuki-Tsuri, supportive strings, were installed on pine tree branches to help the tree endure heavy snow. It is one of the common scenes in traditional gardens in winter.

If we turn to the right along the Daisensui, we will find a unique monument, Yukimi-Doro, a snow-viewing lantern on the stone pavement near the waterside. The samurais appreciated the perfect combination of orange flames in the stone lantern, reflected on the snow on the field and water in the evening. Some garden experts say there is another assumption that Yukimi is the wrong pronunciation and the right one is Ukimi, which means floating object. Actually, there was a tall pole stone lantern standing in the pond, which unfortunately no longer exists, and its flame looked like it was floating with the pole submerged in the water at high tide. To me, it does not matter if it is Yukimi or Ukimi. It’s because both give me excellent images of the taste of the samurais and their aesthetic senses.

The next is the Japanese plum trees, which usually show us beautiful light pink blossoms in full bloom around February. In Japanese custom, pine trees, bamboo, and plum blossoms are an admirable trio, which represent never-die and ever-green for healthy longevity (pine tree), rapid growth toward the sky regarded as good growth (bamboo), and the symbol of the advanced Chinese culture (plum tree originated in China). That’s why we often see pine trees, bamboo forests, and plum trees in traditional Japanese gardens.

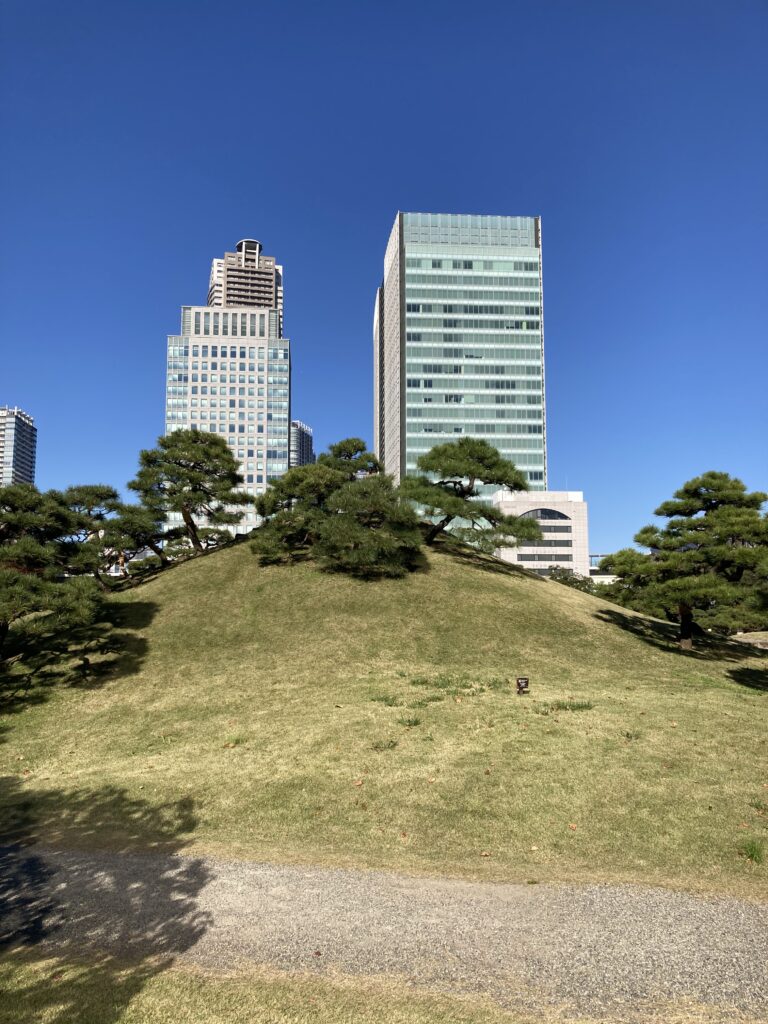

Next to the plum trees is a mound called Oyama, which means “big mountain.” It’s about 2 to 3 meters high. In the Japanese garden’s design concept, all features are compacted and miniaturized to express simplicities and minimalism. So, Oyama is regarded as a massive mountain, and it does not matter if it is really big or not. There is an upward path behind Oyama featuring heavy rocks, which is said to present the power of nature.

From the top of Oyama, we can get a commanding view of the garden, which clearly shows that the pond is a crucial part of the whole design. I feel that all the features, such as trees, rocks, and even small islands, are well-designed as vital parts suiting the pond. I like this picturesque panoramic view because of the contrast between the traditional garden and modern buildings in metropolitan Tokyo.

When we walk down Oyama in the autumn, we might be lucky to come across the autumn cherry blossom called Jugatu Sakura, which means October cherry blossoms. The tree in the photo is not fully blooming yet, but visitors could enjoy viewing cherry blossoms in the brisk and cold weather a week later.

On the foot of Oyama, we can find a path allied with rocks on both sides. It is called Karetaki, meaning dry waterfall. Even though no water is flowing, the rocks and the narrow path inspire our imagination to create a virtual view of the waterfall running through a rocky valley. This design and art concept represent the Japanese aesthetic sense, common in Japanese garden makings and unique compared to other countries.

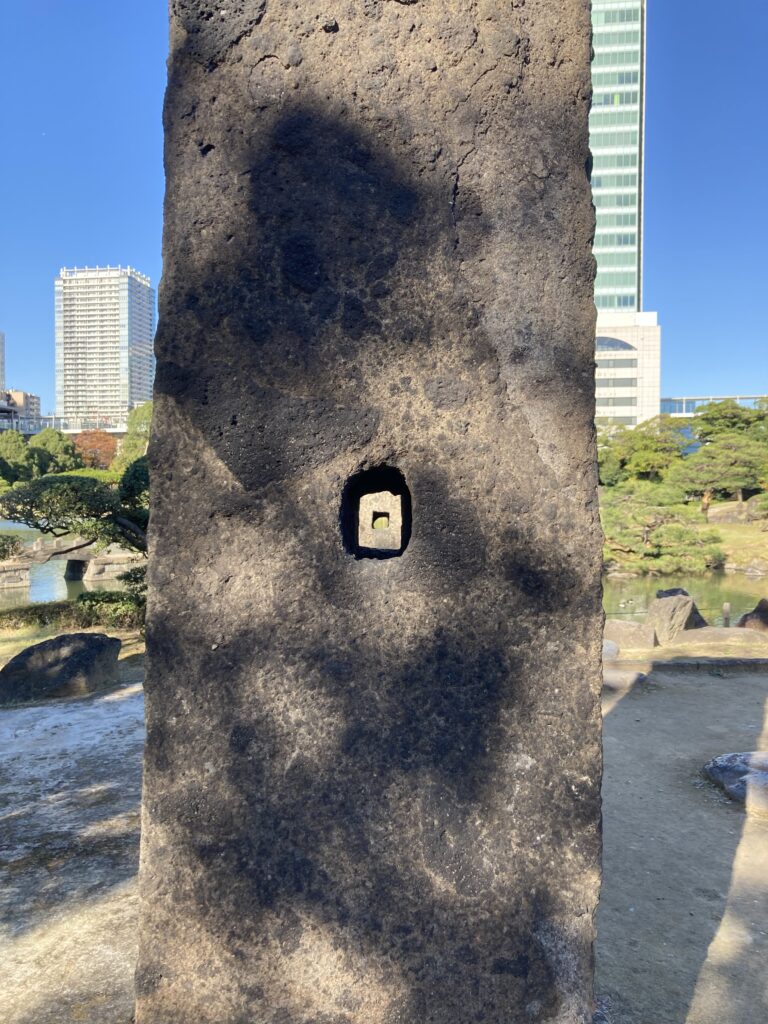

Another remarkable monument in the garden is four stone columns standing on the waterside. The origin of the four pillars has been mysterious. The official release by the garden management office says that they were columns for a tea house, but some experts have pointed out that the location of the tea house differs from one in the old document and map. Some insist that it must have been the sighting device for cannons that might have been set in the early 19th century to defend Tokyo Bay. Another professor claimed that they were the base columns of the terrace where the samurai lord and his guests enjoyed the tea ceremony or party in a higher position, as well as viewing the picturesque landscape of the garden and the ocean view of the seaside behind it. Personally, I will take the third assumption because it gives me a cheerful and amicable impression that many samurais were astonished by the clear vision and enjoyed the vibes of the event in a different atmosphere from other conventional occasions.

No one disagrees that one of the garden’s significant characteristics is Nakashima Island in the pond, which is connected by Seiko-no-tsunami (stone bridge) and Yatsuhashi bridge (wooden bridge). The Seiko-no-Tsutsumi is an homage to and respect for Chinese culture since it was built similarly to the original causeway over Lake Seiko in China. It is symbolic that most samurai admired Chinese culture, technology, and philosophy, such as Confucianism, and its long history since Japan had only access to the world via China then. You can find many Chinese tastes in the traditional Japanese gardens, too.

The mound on the island, called Horaisan or Mt. Horai, comes from Chinese folklore. It is said that a renowned hermit lived there, and then Houraisan became a symbol of wisdom. Many large rocks sticking out means natural energy and the power of wisdom.

After the Horaisan, we walk along the pond and enjoy the scenery on the opposite side beyond the pond.

If you turn your eyes toward the outside, you will find another small mount with stone steps called Kyushakudai, meaning a 2.7-meter-high deck. Just over the end of the steps was a seaside, and when the Meiji Emperor (1852-1912) visited the garden, he stood there and excitedly watched fishermen pulling nets to catch fish, according to the official document of the royal family.

As we are now almost back at the starting point, we can find a path toward the pond. There is no explanation board, but I guess it might be a boat jetty or fishing place because an old record tells us that the shogun family enjoyed fishing when invited to the garden. It said the shogun’s wife was so absorbed in fishing that she told the maids and companions that she did not want to leave there.

Finally, we will return to the tour’s starting point, where we will end it. Another giant stone lantern stands, which looks like it shows us the finishing post or torches a light like a lighthouse. Thank you for joining the Kyu Shiba Rikyu Garden virtual walking tour. I hope you enjoyed it.

Thank you for reading my post.

If you need an English-speaking guide to explore Tokyo, please click “Contact me!” below. I am willing to help you create an unforgettable private tour. Let’s enjoy amazing Tokyo with me!

Please also leave your feedback on this post in the comment box at the bottom. I am willing to hear your opinions, requests, and suggestions.

<Information>

Official Website: https://x.gd/dD6wQ

Location: https://maps.app.goo.gl/U64TqdtUv8Sqq5Zh8

Please click the links to get updated via my X (former Twitter) and Instagram.

X (former Twitter): https://x.com/ToruGuide

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/toruhigaki/

Please visit other posts about the traditional Japanese gardens.

Comment